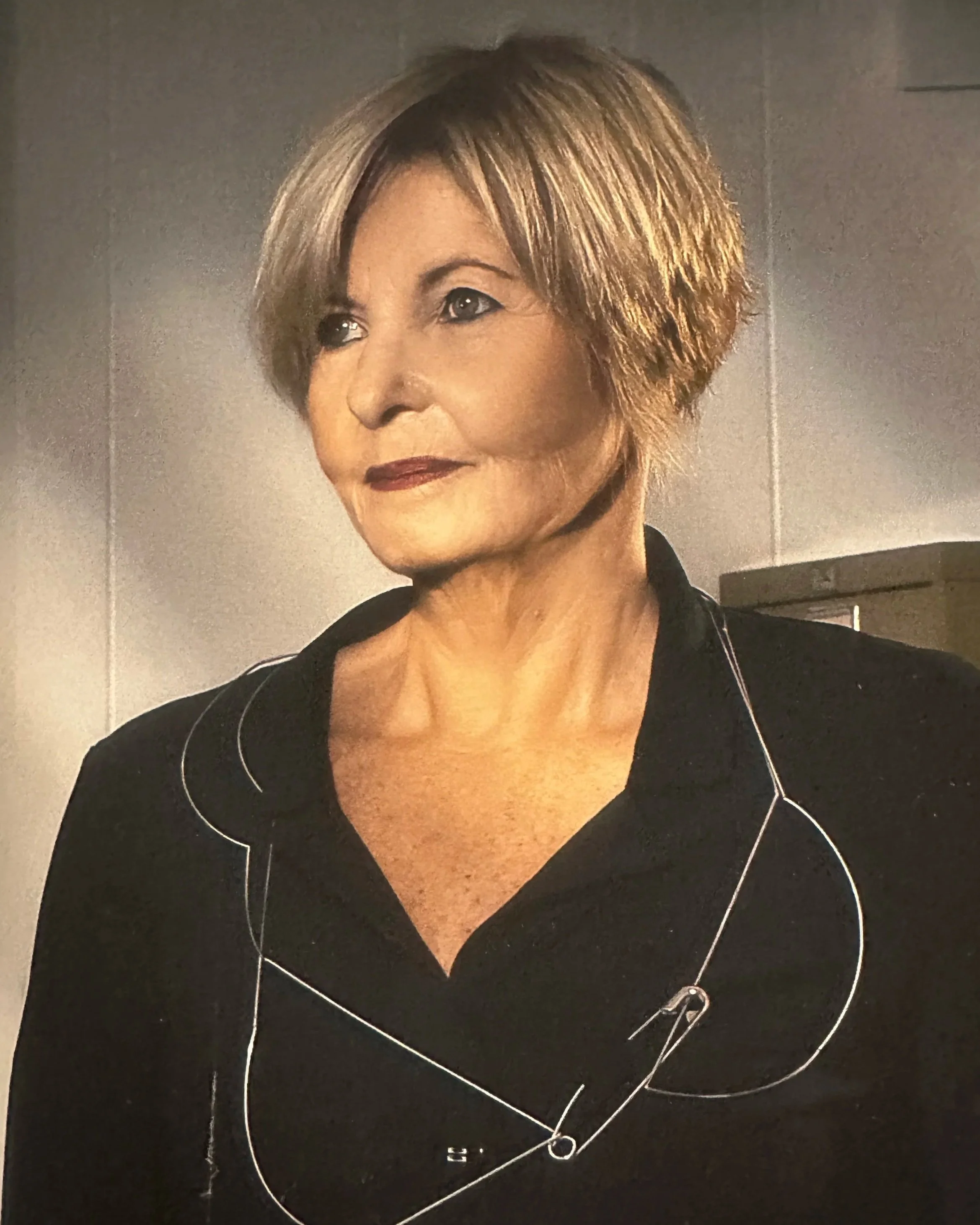

Cathy Leff

Ph. Pedro Wazzan

Stranger #13

Cathy Leff, Executive Director of the Bakehouse Art Complex and Director Emerita of The Wolfsonian-FIU

When Bas van Beek described Cathy Leff as a real force of nature, he couldn’t have found a better expression. From the very first moment I met Cathy, I felt the extraordinary energy that drives her –an energy that radiates passion, curiosity and engagement to everyone around her. Cathy Leff is someone who has always been, and continues to be, deeply open and receptive about what life has to offer. Even when her plans were completely upended, she embraced change and transformed it into something positive. Her journey has been shaped by the challenge of finding the confidence to take on things she had never done before, guided by a strong impulse to help others and to serve the community she lives in. Driven by the conviction that we must all be active participants in society –starting from the hyperlocal dimension– her path has consistently focused on building bridges and supporting communities through art, culture and education. In this conversation, Cathy highlights the importance of the younger generation –in whom she places great hope–, the essential relationship between universities and their cities, the value of remaining curious about the diverse communities that shape a place, and her passion for fashion as a powerful expression of identity.

How would you introduce yourself?

I’m Cathy Leff. I was born in Brooklyn, New York, spent the first seven years of my life in then Rural Connecticut, but was mostly raised in South Florida. I never intended to stay here –I left, went away to school, came back, met somebody, and somehow ended up living in the last place I ever imagined. I realised that everything I planned never really happened, but everything that happened wasn't planned. But it's been fantastic.

I’ve had a great life, one I deeply respect and feel very grateful for. I'm a fairly happy person living in South Florida and loving what I can do here , even though I thought I hated it many years ago.

Could you share some key moments from your professional journey that have led you to where you are today?

I first moved back to Miami in the 70s after university, where I started out studying pre-med. I thought I wanted to be a doctor, though in hindsight I don’t think I ever truly believed it. My parents encouraged me to study abroad, so I spent a year in Spain during the Franco era. That experience opened my eyes to art, architecture, and design, and when I completed my undergraduate degree at Tulane I knew I wanted to shift toward something more visual.I applied for a three year architecture program at Cornell, but came back to Miami between under graduate and then graduate in architecture.During the few months at home in summer. I met someone, stayed, and needed a job –which unexpectedly set everything in motion.

My first roles were in county and city government, in very progressive offices that helped residents navigate public services and evaluate service delivery. Miami in the mid-70s and early 80s was incredibly dynamic –politically, socially, and culturally. I worked in public service for 10 years, focusing on neighborhood planning and revitalisation, trying to help communities participate in shaping their environment during a turbulent period of migration, racial tensions, and explosive growth.I also oversaw the City of Miami’s Art in Public Places and administered all of its cultural funding, so I had a dual portfolio. It was challenging and sometimes scary, but also a fascinating time. Miami was both chaotic and glamorous –the drug era, Miami Vice, the club scene, Versace, the Art Deco revival, all happening at once.

After a decade in the public sector, I was hired by a private collector (Micky Wolfson, editor's note) who was building a visionary collection of decorative and propaganda arts, long before material and visual culture became mainstream fields of study. I helped him think about the future of the collection, worked on real-estate planning for a potential museum, some small scale real estate projects and renovations, and oversaw the Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, which became an important platform for emerging scholarship worldwide. Eventually, I helped negotiate the gift of his collection to Florida International University. I stayed for 20 years as director of The Wolfsonian Museum, integrating it into the cultural life of the city, the intellectual life of the university, and building it into a major global research asset.

In 2014 I stepped away, travelled, and worked with private collectors on long-term planning for their projects. Not long after, a friend asked me to help the Bakehouse Art Complex –an organisation I had originally helped with their city grant decades earlier, which was now struggling. Miami had become dramatically more expensive, and affordable studio space was disappearing. With support from the Knight Foundation, I worked with the organization to help rethink its future–that is what could its future be? To buy time, I raised funds to be able to fill for free 30 vacant studios, bringing in talented Miami-based artists, who were back home and rather than having a studio, had multiple jobs. We partnered with the neighborhood to create a shared vision plan for the future, and developed a masterplan that allowed the organisation to stabilise financially.

Today, Bakehouse is on a strong path, home to a vibrant community of artists and now planning new cultural spaces and the addition of a significant amount of affordable housing for artists and others. Looking back, nothing unfolded the way I expected, but every unexpected turn shaped the work I’ve done and the city I’ve stayed connected to for most of my life.

What has been the greatest challenge you’ve faced in your career?

One of the biggest challenges has been finding the confidence to take on things I had never done before. People often assume that being a woman in a male-dominated environment was the hardest part, but that wasn’t my experience. Many of my role models were men, and perhaps I adopted a more direct attitude because of that. But, I never felt I was denied opportunities because I was a woman.

The real challenge was being thrown into situations where I didn’t initially feel prepared –not because I lacked the ability, but because I lacked confidence. I often had to learn on the job without formal training, and that felt daunting at times. But, just like when I learned Spanish during the year I lived in Spain –terrified to speak for the first nine months– I realised that if you commit yourself, stay aware of what you don’t know, and allow yourself to learn, you can grow into almost anything. That mindset helped me navigate new roles throughout my career.

Another long-standing challenge has been working in the public and nonprofit sectors, where ambition often exceeds resources. After fifty years of fundraising, I still find it hard –I want to see ideas come to life, yet the financial reality is demanding, especially in a fast-paced world where roles and expectations constantly evolve.

More recently, the challenge has shifted toward succession. I’ve always known when it was time to leave an organisation –like when I stepped away from The Wolfsonian Museum. My current role started as volunteer work and evolved into something I’m deeply passionate about. Now I’m thinking carefully about timing: ensuring that the decisions I make today prepare the institution, the board, and the next leader for success. I’m aware that this is my last professional chapter, and while I remain fully committed, I also know there are many talented young people who will eventually take things forward. My responsibility is to leave everything ready for them.

You’ve held director roles in several Miami cultural institutions. How have these roles shaped the organisations’ direction and vision?

At both the Wolfsonian and the Bakehouse, I stepped in at moments when the organisations were, in different ways, like start-ups. The Wolfsonian was transitioning from a private collection to a public institution, and the Bakehouse –despite its 40-year history, was essentially restarting when I arrived, with a small team and a new board trying to understand its place in a rapidly changing Miami.

In both roles, my priority was to rebuild the foundations: strengthening the team, developing the board, engaging stakeholders, and collectively imagining what the future of each organisation could be. Nothing was predetermined, especially at the Wolfsonian. The founder had a very clear idea of the collection he built, but not necessarily how it should serve the public. Because the collection was so unique, the challenge was to identify the right people –curators, advisors, board members– whose collective intelligence could define a path forward.

At the Wolfsonian, this meant integrating the institution into the university system, recognising its academic value, shaping its public narrative, and establishing its credibility from the ground up. The singularity of the collection was a tremendous advantage, but it still required strong collaboration to translate its potential into a public mission.

At the Bakehouse, the challenge was different: Miami’s cultural landscape had evolved dramatically, and the organisation needed to catch up. It required reimagining its role in the community, building partnerships, and creating a vision aligned with the city’s new artistic energy. My role was not to lead alone –I don’t think any director truly shapes an institution on their own, but rather to attract and galvanise the many people whose enthusiasm for the mission helped move the organisation forward.

In both institutions, the vision emerged from collective effort. My contribution was helping bring the right people together, cultivating goodwill, and channeling that shared commitment into a clear, actionable direction.

You’ve often said that artists have a powerful voice –that the more engaged they are with their city and social issues, the greater their impact in shaping a better community. How do you think artists can be more involved in policymaking processes?

I think it starts with something very simple: showing up. Being present at community meetings, paying attention to what’s happening on your block, in your neighbourhood –that’s where real participation begins. In large metropolitan areas like Miami, New York, Los Angeles, Atlanta, or Seattle, we’ve watched the same pattern repeat: artists move into undervalued neighbourhoods, bring energy, visibility, and cultural value, and then get pushed out once the area becomes desirable and rents rise. It’s the reality of a capitalist system.

That’s why artists have to see themselves as citizens first, wherever they are, for however long they’re there. Being an active participant in society starts very locally, and then scales up. Here in Miami, you can get involved at the neighbourhood level, the city level, the regional level. You can vote. You can speak up. There are countless opportunities to shape what happens around you, but many people assume someone else will take care of it. We know now, more than ever, how consequential every level of participation really is.

With the political divide we’re living through in the US, it’s clear how much elections and civic engagement matter. Decisions are made by those who show up, and if you don’t use your voice, you’re essentially surrendering your role in the outcome. And that’s even more true on the hyperlocal issues that affect your daily life.

Artists, in particular, have powerful tools: their work, their visibility, their platforms. Whether through language, visuals, or performance, they often have larger audiences than the average person. When they engage, their voices can carry further and they can help shape conversations and policies in meaningful ways.

You’ve worked closely with universities, particularly through the Wolfsonian –an American university art collection. How do you see the role of universities today, and what is their relationship with younger generations?

Students have a tremendous amount of power in universities –they’re the reason the institutions exist, and we’ve seen over and over that young people are often the ones who drive the biggest social changes. That’s always been true historically. So universities really have a dual responsibility: to educate the next generation and to be active participants in the civic life of the cities they’re part of.

Universities have enormous potential to serve their communities. Many of them are incredibly multicultural, especially here in Miami, and they attract faculty and students who are drawn to the particular character of the region. The interaction between academia and the community is essential, not only for producing research and tackling important issues, but because the city itself often becomes both a laboratory and a source of insight. It’s mutually beneficial.

Here in Miami, both FIU and the University of Miami are deeply involved in community work –helping solve problems, opening dialogue and strengthening quality of life. And that’s important, because the quality of life in a city affects how attractive it is to students and faculty. It’s a loop: the city is a marketplace for the university, and the university is a marketplace for the city. You can’t separate the two.

At public universities like FIU, most students come from Miami and end up staying in Miami, so the relationship is even tighter. These institutions aren’t just educating future thinkers –they’re shaping the future workforce, the economy, the civic landscape. Public universities play an essential role in imagining and building what a metropolitan city can become.

Contemporary art and culture are often seen as distant from the broader community, especially among those without a formal education in the arts. Your mission seems to be about building bridges –connecting art and culture with the community, and even fostering new ones. Can you tell me more about this vision?

I actually think contemporary art should feel more accessible, because it reflects the time we’re all living in. Here in Miami –a place of extraordinary cultural diversity- you can’t talk about contemporary culture through a single lens. To really understand what’s happening now, you have to be curious about the different communities that make up the city.

What we try to do is create spaces where that diversity is visible and represented. When people from different backgrounds come together in the same room, talking, looking, sharing, conversations open up. There are shared experiences, because we’re all living through the same moment in history, but there are also individual stories that shape how we see and create.

Art becomes a bridge. It brings people together and gives artists a platform to speak about their work, their lives, and their perspectives. And it invites the public to be curious, to look at their own time, their own place, through someone else’s lens. Just like with historical art, understanding the life of the artist helps you decode the work. The same is true today.

Your work feels deeply rooted in the city you live in. What’s your relationship with Miami, and what kind of future do you imagine for it?

I’ve lived here a long time, much longer than I ever planned. Miami wasn’t supposed to be part of my story, but it became fascinating and full of possibility. My relationship with the city is a real love-hate one: I love how quickly it evolves, and I also hate how quickly it evolves. Every new opportunity brings a new challenge.

But because my work has always been public-facing, I’ve had the privilege of being deeply engaged in the city’s evolution. Even if my role is tiny, it still feels meaningful. I grew up in what was once a boring place, and I’ve watched it become a multicultural, dynamic, complicated city.

I worry about its future –not just Miami, but any city experiencing rapid growth and concentrated wealth. Who are we designing the city for? Will there still be space for everyone who wants to stay? Rising housing costs and living expenses make that difficult.

But I’m hopeful because of young people. That’s why I miss the university environment –their energy, their fearlessness. They don’t deny challenges like climate change or sea-level rise, they’re already thinking about solutions. Cities need young people to thrive, and we need to create conditions that allow them to remain here.

As the world becomes more urbanised and complex, people specialise in tiny slices of human existence, and that gives me hope. With the ability to communicate, share ideas, and collaborate globally, I’m optimistic –not just for Miami, but for cities everywhere.

Which project do you feel has had the greatest impact on the city of Miami and why?

I think Miami’s greatest advantage isn’t a single project, it’s where we are. We have a beautiful climate, a global-south orientation, and a geographic position that makes the city a natural crossroads.

But if I think about what truly changed Miami’s trajectory, I always go back to Mayor Maurice Ferré in the 1970s. Working for the city during his administration changed my life. I never intended to work in local government, it happened by accident, but his vision was so powerful that it shaped my entire commitment to public service.

He was a globalist, someone who understood Miami’s potential long before the rest of the world did. Because of his background, his travels, and his understanding of geopolitics, he saw that Miami could become a major international city. And during his tenure, it transformed dramatically. What had been a small town began to grow into the global city we know today.

His vision set Miami on its course, making it a place people wanted to be, invest in, and help shape.

I love your regular Bakehouse Fit Check posts on Instagram. What’s your relationship with fashion?

I think a lot of it is genetic. My mother was always into fashion –we didn’t share the same taste, but she was definitely fashion-forward. She had an obsession with shoes, and I definitely inherited that. I’ve always loved fashion, and for a long time it was also a way to deflect attention from myself. When I was overweight, I would spend money on shoes so people looked at my feet instead of my body.

Over time, I realised that fashion is like collecting art, it reflects the moment we live in, our identity, who we are. Now that I’m older, I take myself less seriously. I still love fashion deeply: I appreciate great designers, but I love things I find in thrift shops just as much. I don’t spend a fortune on clothes anymore, but I did for a while because it felt like a way to express myself.

I’m not creative on paper, but I’ve always felt that my body could be a canvas. For most of my life, I used fashion to hide my body. Now, at a weight where I feel comfortable, I use fashion to express how I feel about myself, about the world. It’s also tied to my travels. I adore Japanese fashion from the 80s and youth culture in general. In the 60s and 70s, fashion was a political statement and I still think it is. Fashion, body art, tattoos: they’re all ways of saying who you are and how you identify. For me, it’s always been a vehicle to express my identity.

Is there a dream project you’ve always wanted to realise but haven’t had the chance to work on yet?

If I had a dream project, it would involve conflict resolution, breaking down barriers between people and bringing communities together. It wouldn’t necessarily be in the arts. If I could dream big, with unlimited resources, I’d want to address human-condition issues: hunger, suffering, inequality. There’s so much that needs attention, and it can feel overwhelming.

In my own small way, I’ve chosen to stay hyperlocal, because even small actions can have real impact, even if no one sees them. I love the idea of shaping the future of cities, and that naturally leads to shaping politics and economics too –though those fields are enormous, and I sometimes feel inadequate imagining what I’d do there. At heart, I’m a people person. I think public service is undervalued; it’s not where the money is, but it’s incredibly meaningful.

Could you name a person who inspires you or someone you deeply admire?

Mikey Wolfson, the founder of the museum, would be a fascinating study. He built the institution, assembled the collection, and at 80 years old he’s still travelling the world with endless curiosity. He’s a big thinker, and absolutely one of the people I admire most.

“Micky,

Having you as a friend and collaborator have transformed my life, work, and life view. Your insatiable curiosity and appetite for everything, demanding but generous, with a passion for exploration and knowing. You are an original: unparalleled and indescribable.

You have made the desire to understand human experience and man’s motivation core to the singular collection you have amassed. I’ve been fortunate to work, play and travel with you, witnessing your approach to life and how you create meaningful connections with others and with things. I admire how you navigate life with such authenticity and enthusiasm.

Thank you for the incredible opportunities you’ve provided me and for letting me be a small part of your journey. There’s genuinely no one else like you, and I’m grateful for the experiences we’ve shared.”